Anita Sarkeesian is a feminist pop culture critic who produces a fantastic web series of video commentaries from a feminist/fangirl perspective at Feminist Frequency. She started a kickstarter project to raise money to fund a new video project, which aims to explore, analyze, and deconstruct some of the most common tropes and stereotypes of female characters in games.

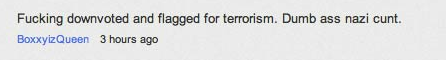

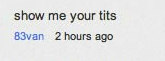

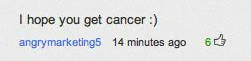

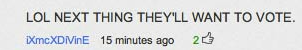

But then the project was subjected to a well-coordinated online harassment effort (by various online video game forums) to take it down. This effort included hate speech on Anita’s Youtube channel, attempts to flag Anita’s videos as “terrorism”, vandalism on her wikipedia page, and the common threatening messages: from typical sexist jokes to threats of violence and sexual assault. Anita has archived a sample of these messages. Here are some examples of the sexist vitriol:

I am speechless…

The only “positive†side of this torrent of comments is that it exposes sexism and misogyny, and ridicules this group of individuals. BTW, Anita not only got the $6,000 she was asking for on kickstarter, she got $44,000 and counting. And there are a lot of male backers as well.

I also found two other very interesting websites of female online gamers that decided to post all the blatant and insidious sexist comments they get when playing: Not in the Kitchen Anymore and Fat, Ugly, or Slutty.

Some of my friends & colleagues suggested that this online harassment does not parallel the “real” world, it is not “real”, and it is only waged by a small and non-representative group of trolls. This is not my field, but the research that I could find online has shown, nonetheless, that online harassment is real and widespread.

Susan Herring (2002) shows that women are mainly the victims of online harassment cases (84%). Such as with the traditional harassment, males tend to be the perpetrators, whereas females tend to be the victims. As Herring (2002) states: “For many female Internet users, online harassment is a fact of lifeâ€.

Biber, Doverspike, Baznik, Cober, & Ritter (2002) surveyed 270 undergraduate students in the US, to explore their responses to online gender harassment in the academia. Findings indicate differences in the perception of sexual harassment by media, i.e. traditional classroom setting versus online. Interestingly, the participants had the same or stronger standards for online behavior: misogynist comments were seen as more harassing online, whereas requests for company were seen as more harassing in the traditional setting. Women also rated online pictures and jokes as significantly more harassing than men, while men rated jokes as more harassing in the traditional setting. Despite these gender differences, the study shows that online harassment is taken seriously by both genders. Women, in particular, seem to be more cautious about sexually explicit online pictures and jokes.

Online harassment not only affects high-profile individuals, such as Anita Sarkeesian or Kathy Sierra (a famous blogger that was continuously harassed and threatened to death), but women in general. According to the Working to Halt Online Abuse, from 2000 to 2011, 72.5% of the 3,393 individuals that reported online harassment were female (22.5% male, 5% unknown). Men also face online harassment, but mostly for being gay or seeming gay (Citron, 2011).

There are different forms of online harassment or hate, but even the “less extreme formsâ€, such as facebook groups named “I know a silly little bitch that needs a good slapâ€, can create an environment of fear, distress, and subservience (Citron, 2011).

In the specific online gaming setting, Staci Tucker (2011) studied griefing and masculinity in online games. As she explains: “Griefers derive pleasure from causing havoc and distress, with little or no ludic gain and often at the expense of their own in-game characters. Griefing can manifest as hate speech, team-killing, virtual rape, unprovoked violence, or theft of virtual currency or items. Griefers are often powerful players, trolls, or even game masters, and can terrorize online communities, as their tactics are difficult to deter and punish†(Tucker, 2011:97-98). Staci suggests that the game industry hasn’t been able to efficiently confront harassment and hate speech in online games, because the main type of player is male, white, and heterosexual.

So misogyny is alive and kicking: “misogyny has by no means gone away, it has instead moved online. The Internet’s easy opportunities for anonymity have a lot to do with it. Bigots act destructively online because they believe that they will not get caught. The Internet has become the place where people can express misogyny with little personal cost. It is the new frontier for hate” (Citron, 2011).

How can we deal effectively with online harassment? Is there any other recent relevant scientific literature?

Please leave me your comments & references below.

Incredible! The world is increasingly dangerous, what is good spreads more quickly, but what is worse yet spread more quickly.

9 gag as the easiest way to have fun e um olhar feminista particular:

http://lentesociologica.blogspot.pt/2012/06/9-gag-as-easiest-way-to-have-fun-e.html