I was on “The Agenda with Steve Paikin” on Wednesday. It was a panel about loneliness with a wonderful group of guests, including THE amazing Louise Hawkley from the University of Chicago. The host was great and the producer was even greater. It was my first TV interview in Canada (and I was a bit nervous), but it was an interesting experience. It made me realize that my training as an academic (or a bad academic, I must say) is not really suited for these media panels. I’ve been interviewed for TV before, mostly in Portugal and Brazil, but in different formats. Homo academicus are used to long debates and are always cautious about clear-cut relationships and unidimensional models of causality – i.e., saying that one factor causes something, since there is always a dynamic interplay of factors, which are often hard to disentangle. We say “there’s a positive association”, “data suggests”, “results are interesting”, and so on. Likewise, it’s extremely hard to say that “the research tells us that” without providing a long list of references.

Based on this particular experience, I realized that I need to be able to explain several complex concepts in 60 seconds (the ‘elevator pitch’ is a useful metaphor here). So, allons-y, my first written attempt:

1. Technological determinism – the idea that technology is the only cause or condition for social change, which also means that its consequences are inevitable and completely independent of us. Technology is the sole driver and powerful force of humankind. When we talk about the “bronze age”, the “stone age” or the “Facebook age”, we are saying that technology is the main engine of human history and that there is nothing else. This perspective is known as technological determinism (there’s actually hard and soft technological determinism, but I’ll leave it to another time) and it is rejected by most sociologists of technology, because a myriad of factors influence social change (e.g., social, psychological, cultural, economic, etc.). And those factors are often intertwined with technology, because technologies are human and social tools. A pencil is also a technology. In fact, technologies are part of society — they are socio-technical systems — meaning that several social factors already influence its design, implementation, use, and evolution. A famous historical example is the development of the QWERTY keyboard: it was not designed to be optimal or efficient, but to minimize typing speed since typists were fast and constantly jamming the keys. But as the QWERTY layout was accepted by IBM and other companies, people got used to it and it became the standard keyboard. This is not to say that technology does not shape or affect us, of course it does, but we also shape and affect technology. For instance, the adoption of any technology depends on a specific social context – that social context can discourage or encourage adoption and will affect both its usage and effects.

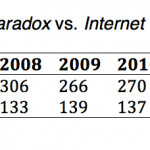

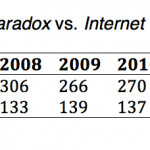

2. Scientific cherry picking – picking one study that supports your argument and ignoring a boatload of other studies. This is visible with the use of the “Internet paradox” of Robert Kraut and colleagues (1998) or the “Alone Together” of Sherry Turkle (2011), when discussing the relationship between Internet use and sociability or social connectedness. For example, Bob Kraut and colleagues published in 1998 a longitudinal study (73 households during 1995-1996) showing that using the Internet for communication purposes was associated with declines in communication with family members in the household, decreases in the size of social networks, and increases in depression and loneliness. Although several scholars criticized the selection of the participants and the fact that Internet users at the time were newbies, not having most of their social ties online, this study became a paradigm of the social effects of the Internet. However, the results were revisited in a follow-up study (1998-1999) by the same authors. In the “Internet Paradox Revisited”, Kraut and colleagues (2002) studied the long-term impact of Internet use on members of the original sample and found that the negative effects were no longer observable. Interestingly, their original study is constantly cited and mentioned by media pundits – and scholars alike – but their 2002 study is often forgotten. To conclude, two important points here: first, science is made of constant replication (one study is not enough), and 2) we can only know if scientific results are well grounded and good (valid and reliable) when we consider how the study was done (methodology), including how the participants were selected (sampling), how the data was collected, and what tools were used to analyze that data. The “scientific halo effect” is also cleverly used to enhance cherry picking — just mention one study conducted by a Professor from MIT or Harvard and that always seems to be enough to convince others. Fortunately, good science works hard at avoiding (or trying to avoid) cognitive biases.

Note: Although this would not be part of my elevator pitch and it’s a simple descriptive indicator, I looked at the number of citations each paper has on Google Scholar and even when adjusting for the different publication dates (first paper was published in 1998, second one in 2002), the original article is considerably cited more often in the last 10 years (click to enlarge):

3. Impression Management – It’s what we do to make others see us the way we want others to see us (usually in a good light). Impression management efforts are the techniques, practices, and actions that we use to control our we present ourselves and how we act in social environments. The way I dress, walk, and talk to a co-worker or a friend, are often crafted to convey a certain persona. So, the common belief that there is only “impression management” online (or on Facebook) is quite interesting, because we are always crafting personas for public consumption – be it online or offline.

4. Difference between a friend and an online contact – An online contact is someone you add online, for instance, to Facebook or Twitter. A friend is someone you share something with, besides an electronic link. You can have, of course, a virtual friend, i.e., someone that you share and feel close to online. But an online contact is not necessarily a friend: we tend to use adjectives to qualify our friends, when someone says: “He’s my Facebook friend” we know that the expression sets a tone for that type of relationship, which is different from “He’s my friend” or “He is my best friend”. When I talk about social connectedness, I talk about meaningful social relationships; those relationships that bring us joy, satisfaction, and support. The evidence overwhelmingly shows that when the Internet is used for communication, it has positive effects on social connectedness (at least, so far, controlling for a variety of sociodemographic factors, and even for “socially isolated” groups). By overwhelming evidence I am referring to the abundant and systematic research done in the last ten years (+50 worldwide studies…would be dying to list all the references at this moment). Now, the Internet might have positive or negative individual effects depending on how it is used: if you use the Internet mostly for individual entertainment, you can’t expect your levels of social connectedness to increase (e.g., several studies about introverted people show that they mainly use the Internet for entertainment; contrary to the idea that they use it for communication in order to compensate for their perceived low social skills). Having said that, there are issues that I anticipate will affect social connectedness in the future – hypotheses that have to be, of course, properly tested – such as privacy issues or cyberbullying.

How did it go? A bit long still, but I’ll work on it.

© Steve Paikin

© Steve Paikin